What is turbo lag and why does it happen?

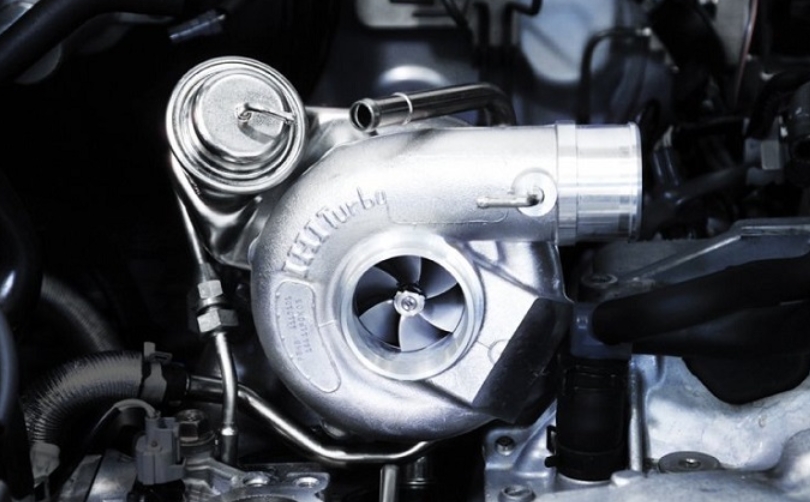

Turbocharging primarily increases the torque, but also the power of the internal combustion engine. It uses the energy of the exhaust gases, which would otherwise pass through the exhaust without any use. But turbos also have their drawbacks.

What is turbo lag

Turbo lag or turbo hole can be translated very simply as a delay or delay of the turbocharger. This means the delay between the moment when we step on the pedal at lower revs and when the turbo actually starts to supercharge. It’s a well-known effect that ordinary motorists began to perceive with the massive proliferation of turbocharged diesel engines at the end of the last century. A typical example of a car that has quite noticeable turbo lag is the first Octavia with a 1.9 TDI engine. There it was really enough to feel that when you step on the gas pedal, nothing happens for a while, and after about a second, something that fans of these engines call a “kick in the back” comes. Quite honestly – he’s actually not that much of a “kicker”, but we don’t want to spoil anyone’s illusions. In short, it was felt that the driver had to wait a while for a proper pull with the unit not turned on.

Causes of turbo lag

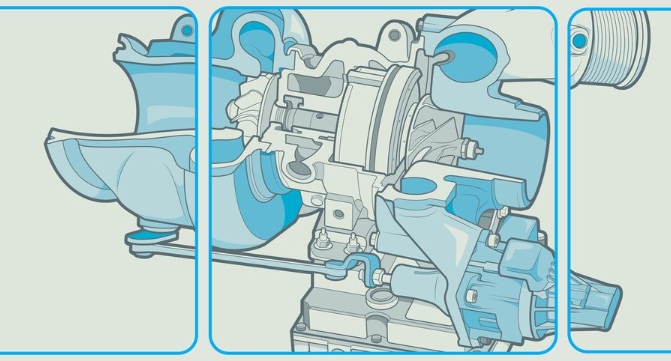

When we look at how a turbocharger actually works, it is quite logical that there must be some delay. The driver steps on the gas to accelerate more forcefully, which causes the throttle to open and thus supply more air. At the same time, more fuel will start to be injected. The engine therefore burns more mixture and produces more exhaust gases. These go to the turbocharger, where they are resisted by the turbine wheel, the blades of which the faster flowing gases rest against and start spinning it. It won’t happen right away either, because the center of the turbo weighs something, and the heavier it is, the longer it takes. In addition, the whole process is hampered by the fact that at the moment when gases are leaving one cylinder through the open exhaust valve and its piston goes to the top dead center, another cylinder is at the end of the exhaust phase, the piston in it goes to the bottom dead center, but the exhaust valve is only begins to close. There is thus a certain overlap, when two cylinders connected by one pipe have open exhaust valves and there is overpressure in one of these cylinders, while a vacuum is created in the other. Part of the gases that should go directly to the turbine is therefore drawn back and the flow is not constant. This effect obviously reduces the speed of the turbo and its overall efficiency.

The speed of the turbine wheel is, of course, the same as the speed of the wheel in the compression section. That’s where the important thing happens – the compressor wheel starts to create pressure (charging pressure) and drives the air supplied by the intake into the intercooler, where it cools and then eventually into the cylinder. It is only when all this happens that the driver begins to feel an increase in torque.

The problem with the effect described above is that the gas (air and exhaust) compresses very easily, and in a turbo this happens several times during acceleration. Of course it takes some time each time and with a little simplification we can say that the sum of all these times needed to compress the gases = turbo lag.

An automatic transmission can also cause a delay

Every now and then it happens that even today, when car companies are quite good at suppressing turbo lag, someone complains that they have to plan a bit when overtaking. It’s not necessarily due to turbo lag, but rather the automatic transmission. In particular, double-clutch gearboxes work in such a way that they have to prepare for a higher gear before engaging it. If the driver drives rather slowly and accelerates smoothly, the gearbox shifts from fourth to fifth at somewhere around two thousand revolutions. But if, for example, while driving in fifth gear at a steady speed, the driver suddenly presses the gas pedal and the control unit evaluates that it must downshift for rapid acceleration, instead of the prepared sixth, it must shift a quarter lower, i.e. the third, which it did not expect at all and therefore does not have prepared (it is this is again a very simplistic example, but in its essence it is so). This takes well over a second of time, and the driver can then incorrectly attribute this sometimes quite long delay to turbo lag.